By Jingwei Jia and Mervyn Tang

The operational phase of China’s national emission trading scheme (ETS) has begun, with the measures that form the legal basis of the scheme coming into effect on Feb. 1 and trading set to begin in mid-2021. The Ministry of Environment and Ecology, formed in 2018, is the scheme’s main regulator. Regional pilot schemes to test processes, rules and market infrastructure development have taken place over the past three years, with the National Development and Reform Commission releasing the initial ETS framework in 2017. The regional pilots have explored how carbon markets could function in different structures, including allocation mechanisms, sectoral coverage and the use of offset credits and carbon derivative products.

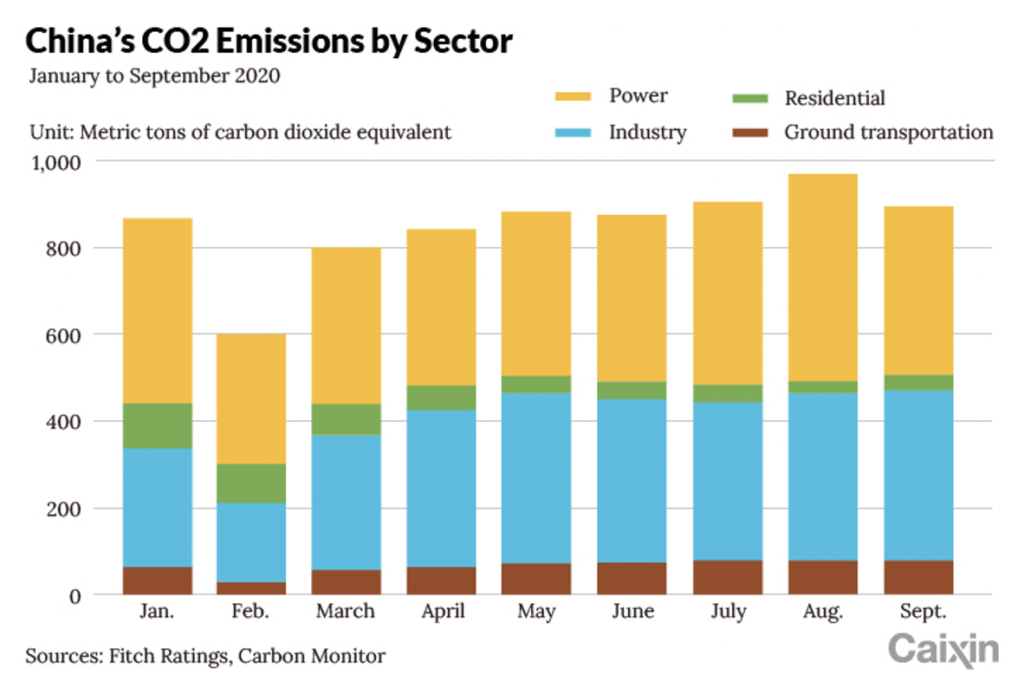

The national ETS will initially only cover the power sector, which accounts for around 30% of domestic carbon emissions, but will ultimately cover other sectors, including petrochemicals, chemicals, building materials, steel, non-ferrous metals, paper and domestic aviation. Certain sectors that make up a significant proportion of overall greenhouse gas emissions, such as transport, agriculture and construction, are still excluded from the scheme.

The first ETS compliance cycle runs from Jan. 6 to Dec. 31, 2021, during which entities need to report and verify emissions, and trade allowances to meet any obligations. The first cycle covers emissions from 2019-2020. Entities with annual emissions of around 26,000 tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) — which equates to total energy consumption of more than 10,000 tons of coal equivalent — in any year over 2013-2019 are required to participate in the first compliance cycle; 2,225 power generators meet this criteria. Entities that participate in the national ETS will no longer be part of regional scheme pilots.

Participating entities have an obligation to surrender allowances if their verified emissions exceed their free allocation, which they will need to acquire from the market. Obligations are capped at 20% above an entity’s free allocation, limiting the compliance burden, at least in the initial cycle. Obligations for gas-fired plants are even lower, capped at the level of their free allocation, as part of the government’s plan to promote the development of gas-fired units. Failure to report or meet compliance obligations could result in a fine, although the maximum level is a low 30,000 yuan ($4,644). Gaps in verified emissions and surrendered allowances could also lead to a reduction in future allocations.

Allowances based on carbon intensity

Allowance allocation is a key factor in the success of the ETS. The Ministry of Environment and Ecology updated its draft allocation plan for the power sector in November 2020, with first compliance cycle allocations determined by four benchmarks for different subsectors. The benchmarks, which are based on the size and fuel type of power generators, include conventional coal plants below and above an installed capacity threshold of 300 megawatts, unconventional coal plants and natural gas plants. There are further adjustments based on technology used and output capacity usage. The standards will tighten as the allocation plan is developed over time.

Entities will initially receive allowances at 70% of 2018 output multiplied by the corresponding benchmark factor. Free allocations will subsequently be adjusted in accordance with verified emissions for 2019-2020 as reported by the entities. However, data reporting and collection may be delayed due to the disruption caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

The use of carbon-intensity benchmarks, rather than absolute emission caps, differs from the European ETS and is more likely to drive competition within benchmark groups — for example, on low carbon technology use and improved energy efficiency — rather than encourage substitution across benchmarks, such as from coal to natural gas.

The carbon-intensity model may also better suit China’s economic conditions, given the rapid pace of economic growth and rising energy demand. These factors can make it more challenging to set fixed absolute emission levels without inadvertently constraining growth prospects. Multiple benchmarks also moderate the impact on entities while the scheme gets up and running.

We expect China to reduce the number of benchmarks and apply absolute carbon emission caps over time as efforts to decarbonize intensify. The 2020 China Carbon Pricing Survey shows that a majority of respondents prefer a transition towards a single benchmark in the long term. This tightening should encourage the transition from high carbon-intensity fuel sources to clean energy, rather than just improvements in carbon efficiency.

Fitch expects a limited initial impact from the national ETS in light of the benchmarks used in the first cycle and caps on compliance costs. This reflects how the initial phases of the scheme are being used to explore and test market mechanisms and the system infrastructure.

Impact to increase as rules tighten

However, we expect rules to tighten over time as China tries to achieve a 65% reduction in carbon intensity per GDP unit by 2030, as pledged by President Xi. The pace of tightening will in part depend on the strength of the post-pandemic recovery, as policymakers attempt to balance growth considerations with decarbonization goals. Technological change will also be a significant factor, with decarbonization likely to occur quicker if there are substantial breakthroughs that improve the cost competitiveness of renewables, for example, battery and hydrogen storage.

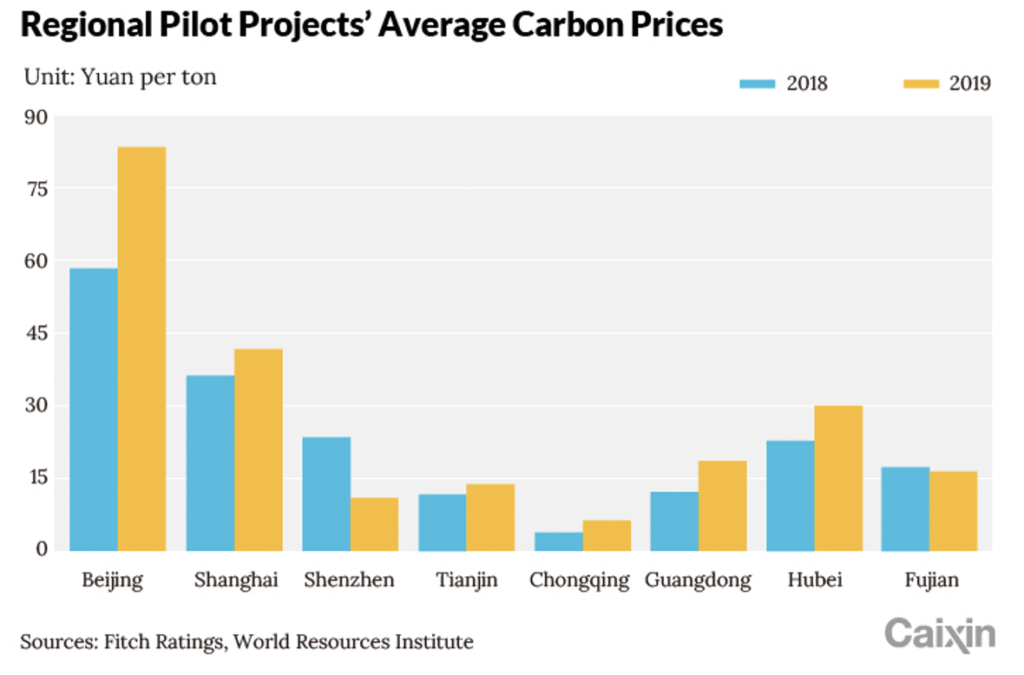

The 2020 China Carbon Pricing Survey points to an average estimated carbon price under the national ETS of 71 yuan ($11) per ton by 2025 and 93 yuan per ton by 2030. This is similar to the average carbon price seen in Beijing’s 2019 regional pilot and higher than that in other regional schemes. However, it is much lower than European ETS prices, which reached nearly 38 euros ($45) per ton in February after the 2019 introduction of the ETS Market Stability Reserve. The scheme substantially reduced the surplus of allowances in the market. We expect similar developments in China as ETS allowances are reduced over time and the scheme moves towards an auctioning mechanism.

Higher carbon prices, particularly if the ETS ultimately moves towards a single benchmark or absolute emissions cap, would encourage entities to shift away from carbon-intensive fuel sources and towards clean energy. China’s total energy consumption remains highly dependent on fossil fuels, despite rapid growth in renewable capacity spurred by subsidies over the past decade.

The shift towards applying costs to carbon emissions is occurring at the same time as subsidies for renewables projects begin to be phased out. Improving the cost competitiveness of renewables has allowed policymakers to remove subsidies while maintaining higher renewable generation targets. China has pledged to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 25% and to boost the installed capacity of wind and solar to more than 1,200 gigawatts (GW) by 2030. We believe this is an achievable target, even without subsidies, given the record of lowering costs. The combined installed capacity of solar and wind reached 934 GW by December 2020.

The expansion of the national ETS beyond the power sector could encourage operational changes, such as relocation. CRU research pointed to examples of this occurring in the aluminum smelting sector, where capacity was relocated to areas of low-cost hydropower due to renewable incentives and perceived regulatory risks from coal-based generation. The competitiveness of carbon-intensive exported goods, such as steel, could also weaken as ETS coverage expands and rules tighten. EMEA steelmakers have suffered competitive pressure in recent years owing to high carbon prices and a lack of ETS coverage in rival markets. However, competitiveness considerations will depend on the pace of tightening of the ETS in China compared with other markets.

Offsets to encourage low-carbon projects and renewables

The initial ETS allows 5% of verified emissions to be offset through China Certified Emissions Reduction (CCER) credits; one unit of CCER can be used to offset one equivalent of CO2 emissions. Offsets could come from a variety of sources, including renewables, carbon sinks (such as forestry) or the utilization of methane. Specific rules for the incorporation of CCER into the ETS are still under revision by the Ministry of Environment and Ecology, with timelines yet to be published.

CCERs started trading in 2015 after the launch of the national registry of Voluntary Carbon Emission Reductions. The National Development and Reform Commission halted CCER trading in March 2017, but trading resumed in May 2018 and saw volume rebound; CCERs totaling 256 million tons of CO2 had been traded on the primary and secondary markets as of October 2020.

China had registered 1,047 CCER projects as of April 2020 and 287 CCER projects had their emission cuts approved for issuance. We expect the use of offsets under the CCER scheme to expand as the national ETS develops, with demand particularly high from entities in carbon-intensive industries, where carbon abatement is costly or hard to achieve.

So far, all of China’s regional pilots have allowed entities to use CCER credits to fulfill their compliance obligations, with quantity restriction of 1% to 10%. Beijing, Guangdong and Fujian also permit certain carbon-emission reduction products other than CCERs during the compliance period, including energy saving and forestry carbon sequestration. Eligibility of project types varies among markets, such as on the use of hydropower, non-CO2 industrial greenhouse gases — such as hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons and nitrous oxide — as well as fossil-fuel based and waste-heat power generation, according to the Environmental Defense Fund.

The goal of deploying an offset mechanism in a carbon market is to direct decarbonization efforts towards areas of lowest cost, including sectors and projects that are not covered under the ETS. Success will depend on the design of the offset mechanism and how it is incorporated in the ETS. Loose eligibility requirements could lead to an oversupply of offsets without driving progress on carbon reduction. Oversupply of offsets could also drive down offset prices, reducing the incentive for businesses to investment in low carbon technology and energy efficiency if compliance requirements can instead be met through offsets.

Jingwei Jia and Mervyn Tang are both analysts at Fitch Ratings.

This piece originally appeared in Caixin.