By Kevin Mo

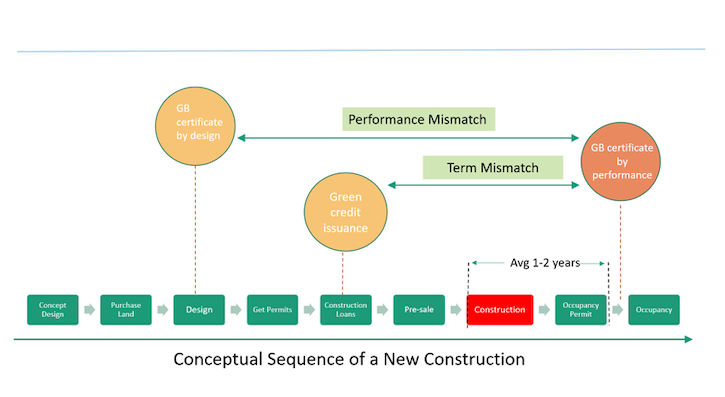

In March 2019, the Chaoyang District government in Beijing announced the historical signing of a green insurance contract for ensuring green performance of a commercial building. Less than two weeks later, another green insurance contract was signed in Qingdao, Shandong Province, for securing ultra-low energy performance of eight residential buildings. Only three years after a Paulson Institute policy paper originally proposed a green insurance model, a series of insurance products were developed, and two green insurance contracts have been signed, effectively breaking the two longstanding roadblocks impeding green transformation of the building industry worldwide: performance mismatch between building design and operation, and term mismatch between credit issuance and performance verification.

Green Buildings & Energy-Efficient Buildings

Green buildings have long been touted as a promising solution to transform the building industry into a more environmentally responsible one, featuring energy efficiency, resource efficiency, healthy indoor air quality, and a series of other green considerations.

One of the most popular green building certification programs has been the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program, developed by the U.S. Green Building Council in 1997. Around the same time, the U.S. and China started to collaborate on a groundbreaking project to demonstrate an energy-efficient office building in Beijing, eventually owned by China’s Ministry of Science and Technology. The building was occupied in 2004 and earned the first LEED certification in China.

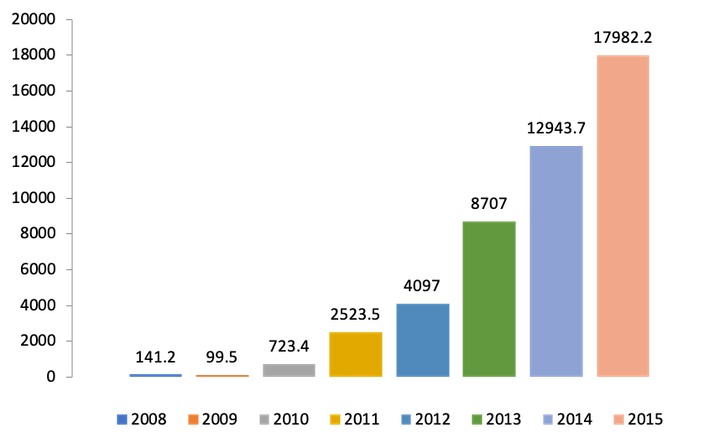

However, the concept of energy-efficient building in China originated much earlier. The first national standard for energy-efficient buildings was adopted in 1986, but was not enforced until two decades later. China started to develop its own national green building certification standard in 2006, dubbed the “Three-Star Program” (TSP), and certified its first green building in 2008. In the program’s first five years, the total floor area of TSP-certified green buildings was less than ten thousand square meters, almost negligible compared to the 10 billion square meters of new buildings constructed in China over that period.

In 2013, the State Council released a National Green Building Action Plan, significantly jumpstarting the green building market. In the following three years, TSP certified 472 million square meters of green buildings, surpassing LEED as the world’s top green building certification program by total certified floor area.

Ever since TSP came into effect, a series of new concepts have emerged in the Chinese building market, including passive buildings, ultra-low energy buildings, zero energy buildings, healthy buildings, and low carbon buildings. Nevertheless, these concepts have always meant to emphasize actual performance improvement.

China’s Green Building Program Has Grown Quickly Since 2013 (10,000 square meters)

Performance Mismatch between Building Design and Operation

Due to the inherent characteristics of the building industry, a common problem facing green buildings and energy-efficient buildings has been the performance mismatch between design and operation. Green building design cannot guarantee that the actual building performance will be in line with the green design. By the same token, the goal for energy efficiency set at the design stage for an ultra-low energy building does not ensure measured energy parameters after occupancy. But developers prize the green design labels issued before construction, because they allow developers to charge a “green premium” in the sales stage.

To address the performance mismatch between building design and operation, one solution has been to add another layer of certification for the performance stage after a building has been occupied. But many developers simply ignore the second certification—by the time a building is ready for its performance rating, the developers have already made out with a ‘green’ profit. In fact, among all of China’s certified green buildings, less than five percent hold green performance certificates; most are green-certified by paperwork only.

The performance mismatch between design and operation has been a universal impediment to green building and energy-efficient building programs around the world.

Term Mismatch between Credit Issuance and Performance Verification

As if this problem was not serious enough, governments worldwide promoting green development often jump on the bandwagon by offering incentives or subsidies to green buildings. It is convenient for governments to demonstrate their green commitment by incentivizing certified green or energy-efficient buildings. For example, a local Chinese government subsidizes ultra-low energy buildings by RMB 1,000 yuan (about $150) per square meter. But if those buildings are certified using design blueprints only, the gap between design and operation certifications will be further widened due to the subsidies. And when government incentives reward undesirable behaviors, it builds nothing but distrust between developers and consumers, eventually damaging the credibility of green and energy-efficient buildings and making green transformation even more challenging for the building industry.

The green building market only gets further skewed when bankers enter the fray.

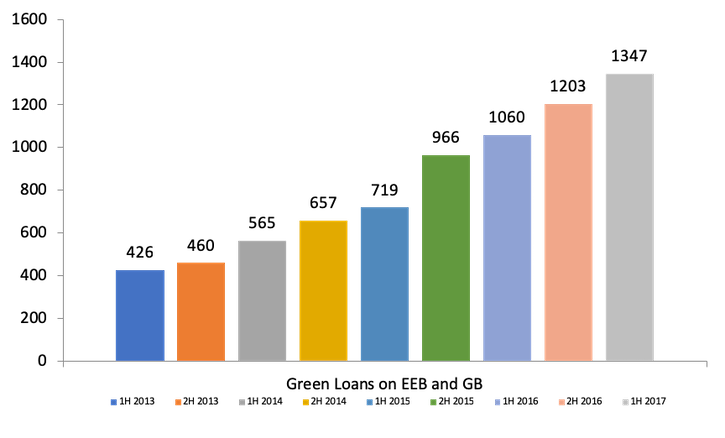

A December 2017 report released by the former China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) showed that 21 major Chinese banks had issued green credits totaling RMB 8.22 trillion among 12 green categories in the first half of 2017. Category Nine, for green buildings and energy efficient buildings, was issued a whopping total of RMB 730 billion in green credits from 1H 2013 to 1H 2017.

The banks have decided whether or not a building is green or energy-efficient based on design certificates. Therefore, when the actual performance after construction does not match design performance, the concessional rate of construction loans amplifies the mismatch issue. But the banks probably cannot be blamed for missing due diligence, as they simply do not have the necessary institutional knowledge to make good judgment calls on these matters.

What if banks could issue green credits based on operational performance certificates, rather than design certificates? Regrettably, it would be simply too late, since construction loans are made before construction and operational performance is verified after construction.

Green building programs around the world have started to realize that the performance mismatch between design and operation has become the major bottleneck for market development. In China, one proposed solution is to cancel the green building certification for design and only keep the certification for the operational stage. If this ultimately gets implemented, it would remove the performance mismatch between building design and performance.

However, the term mismatch between credit issuance and performance verification still persists. Even worse, the foundation of green credit collapses, as green design labels disappear. Without a certificate to prove the green face value before construction, banks cannot issue any green credit under the current green credit guideline for green and energy-efficient buildings.

Banks are in urgent need of a solution.

Green Loans for Energy-Efficient and Green Buildings are Rising Steadily (100 million RMB)

An innovative scheme to break the deadlock

In 2016, the Paulson Institute published a policy paper ‘Financing Energy Efficient Buildings in Chinese Cities.’ sponsored by the Bloomberg Philanthropies. The paper identified huge financial needs, as well as gaps and mismatches in the green building market. It proposed an innovative model that introduced the concept of green insurance for scaling green performance-centered buildings, addressing the two mismatches: one between building design and operation, and the other between credit issuance and performance rating.

In 2017, People’s Insurance of China (PICC), the largest property and casualty insurance group in Asia, signed an agreement with the Paulson Institute to develop a line of insurance products based on the concept.

In 2018, the city of Beijing—already one of the most active cities in promoting green buildings—agreed to pilot the green insurance model for green buildings, with funding support from the World Bank and Energy Foundation. Just recently, the coastal city of Qingdao also joined the effort by starting to pilot the green insurance model for ultra-low energy buildings.

The two newly signed insurance contracts in Beijing and Qingdao applied the same model for ensuring two different building performances: one for green building parameters and the other for energy use indicators, thus proving the robustness of the model. The signings signified the embodiment of the green insurance concept proposed in the Paulson Institute policy paper. They also marked a perfect representation of the Paulson Institute’s “think-and-do” motto.

There remains much left to be done

The concept of the green insurance model to break the deadlock is not exceedingly difficult to understand. Under the model, a green developer buys an insurance policy before construction to ensure a building’s green performance after construction. A banker then issues green credits based on the insurance policy. Once the building is constructed and occupied, the insurance company will be liable to repair or pay if performance ratings do not meet the original promise.

However, implementation of the concept proved to be much more challenging under the pilot.

First of all, the insurance company and the bank participating in the pilot differed in risk-averse preferences. Under current regulatory policies, the bank had little flexibility to adjust its credit issuance practices. An originally designed insurance-banking interlocking mechanism ended up not being implemented. If banks were to issue green credits based on performance-guaranteed insurance policies, it would significantly boost interest from green developers in ensuring green performance after construction. Without a construction loan, developers cannot start construction.

Interestingly, at the time when the insurance model was proposed, China’s banking regulatory commission and insurance regulatory commission were two separate agencies. By the time the Beijing pilot started, the two agencies had merged into one agency: the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC). It is now possible for CBIRC to promote the insurance-banking interlocking initiative to support green development. The newly established CBIRC also shall have incentives to encourage the insurance-banking interlocking mechanism for green buildings.

Improvement of all related regulations and policies proved to be a critical tipping point. Central and local government agencies must streamline current pro-green policies to foster more market-oriented innovations, including the green insurance model.

Furthermore, banks, insurance agencies, and governments must share credit reports among each other so that all involved parties can track and share the profile of a building project, from design to construction to occupancy.

Finally, the most important task that has not yet been fully achieved is to quantify the insurance premium based on the risks presented by developers, projects, green levels, and other factors. Hopefully, the two projects in Beijing and Qingdao will help improve the actuarial model.

Nevertheless, the two signed contracts proved that the green insurance model is capable of breaking the deadlocks. Further pilots will test a policy framework that can scale performance-based green buildings through coordinated efforts between green insurance and green credit. The Paulson Institute is committed to helping expand this innovative solution to addressing crucial challenges to green building development in the world.