By Angel Hsu, Yuqian Peng, and Kaiyang Xu, Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies

China announced its official climate pledge last week, and although most of the details are not surprises–the document closely resembles last November’s historic climate agreement with the United States–the nation’s intended nationally determined contribution (INDC) included several indications that China is serious about addressing climate change.

The key points from China’s 2030 pledge are:

- Carbon intensity (e.g., carbon dioxide emissions per unit GDP) will be reduced 60 to 65 percent from 2005 levels.

- The share of non-fossil fuels will increase to 20 percent of the primary energy mix.

- A Congo’s worth of forest —4.5 billion m3—will be added relative to 2005 levels.

The world’s largest consumer of energy and top emitter of carbon emissions, China has the ability, like no other country, to shape the fate of the global climate. Unpacking what China has pledged gives us a critical barometer for understanding what is needed from the other countries that have yet to submit their INDCs. Here are a few key takeaways:

1. China is on track to complete its previously committed 2020 target.

In its INDC announcement, China indicated progress towards its 2020 target, which Chinese leaders announced at the 2009 Copenhagen climate talks and adopted as part of the nation’s 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015). China committed in that Five-Year Plan to reduce carbon intensity 40 to 45 percent from 2005 levels by 2015. According to this year’s INDC, China has reduced carbon intensity 33.8 percent to date.

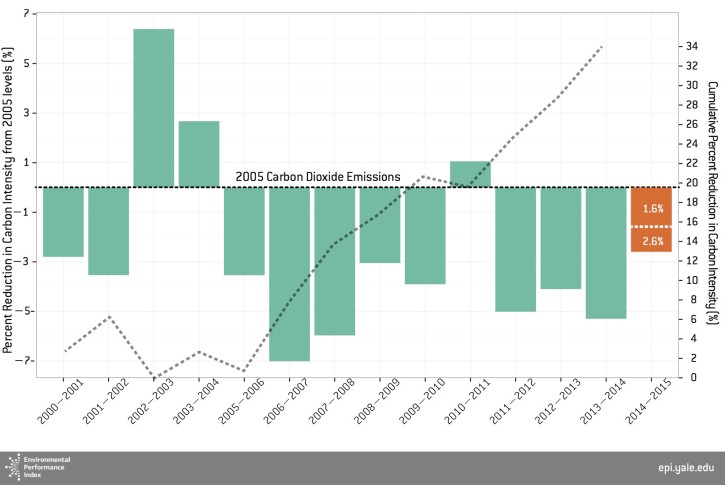

This means that China only needs to reduce carbon intensity by about 1.6 percent to achieve the 12th-Five Year Plan’s low-end goal (16 percent) or 2.6 percent to achieve the pledge’s high end (17 percent, see Figure 1). Given that an average of 5 percent reduction in carbon intensity was achieved in each of the previous years, China should easily achieve the remaining amount of its 12th Five-Year pledge, boding well for attaining the 2020 goal.

2. China’s target per capita carbon emissions would peak at a level much lower than European countries’ and the U.S.’s carbon intensity peaks.

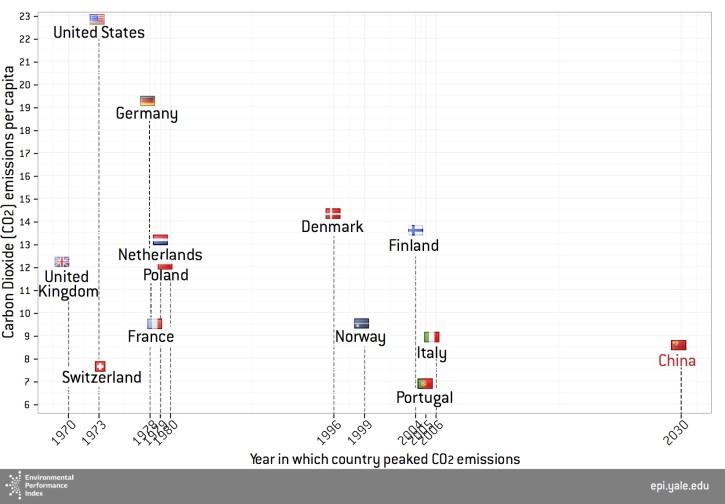

Projections estimate that when China peaks its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2030, it will reach an average of 8 tons of CO2 per person. By contrast, U.S. per capita CO2 emissions in 2012 were 16.23 tons. China’s CO2 emissions per person will also never approach per capita levels of many European countries when these nations reached their respective peak emission intensities (Figure 2), including Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands.

3. China’s forestry target will intensify pressure on other land-uses, including agriculture and urbanization.

China’s target to increase its forest stock volume by 4.5 billion m3 translates to a 30 percent increase from 2005 levels. So far, in the 12th Five-Year Plan, China reports that it has already achieved roughly half of its goal (2.188 billion m3), although satellite data show that China experienced a loss of 6.3 million hectares of forest cover from 2001 to 2013 while gaining only 2.4 million over the same period.

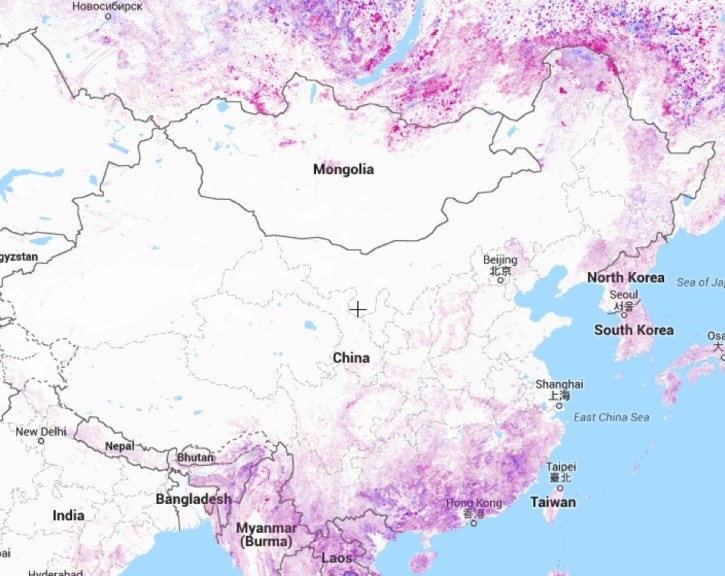

With agriculture and urban expansion putting tremendous pressure on available land, where will the new forests grow? In 2009 China had 0.08 ha of arable land per capita, 40 percent of the global average. Compounding the relative scarcity, 310,000 hectares of arable land were lost in 2006, 84 percent of which were converted to urban, built environment. The Chinese government’s goal to increase its urban population to 60 percent by 2020 will undoubtedly create additional challenges for balancing agriculture and forestry. More than half of the nation’s forest cover loss has occurred in China’s most populous and wealthiest provinces, such as Guangdong, which boasts the country’s fourth highest per capita GDP (Figure 3).

4. China plans to increase reliance on nuclear energy to achieve its 20 percent non-fossil energy target.

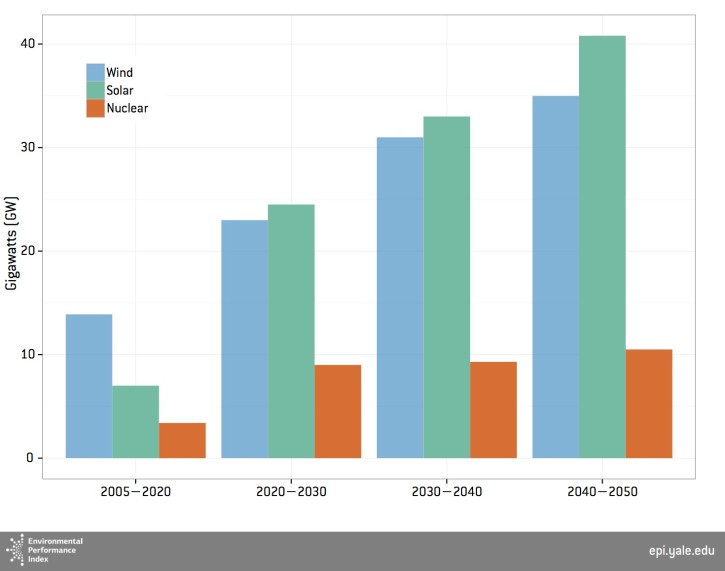

Renewables like wind and solar power will comprise the bulk of the 20 percent non-fossil target, though China will also increase the share of nuclear power generation over the next several decades. China is home to nearly half of the world’s nuclear reactors, with 26 commercial reactors operating and 24 more under construction. The gigawatts generated from nuclear sources is expected to more than double between 2020 and 2030 (Figure 4). The World Nuclear Association projects that nuclear online capacity will provide about 10 percent of China’s total electricity generation in 2030. In terms of hydropower, which has been controversial in China due to large-scale projects like the Three Gorges Dam, its share of the overall energy mix is only expected to increase slightly from around 7 percent in 2020 to 8.5 percent in 2030.

5. This is the first climate pledge that mentions public participation.

Whether China will be able to achieve its INDC targets, given uneven environmental policy implementation in the past, is a major question. Part of this past criticism has been due to China’s emphasis on top-down, command and control methods to implement its carbon and energy reduction goals. Its use of an “iron fist” to shut down dirty, inefficient factories and power plants to ensure that targets are met has long been the subject of international criticism. These hierarchical policies, however, are shifting to encompass a position of more public outreach and inclusion. Along with last year’s landmark Environmental Protection Law revisions, China’s INDC includes language proposing “low-carbon living” and a “social participation mechanism” to engage the public to help achieve the country’s carbon goals. This is the first time China has mentioned enlisting the public in a climate pledge to the UNFCCC, signaling a heightened awareness that the government cannot achieve its ambitious pledges without popular support and assistance.

The Road Ahead to Paris

China’s pledge has set the bar for other large, rapidly-developing countries and the remaining half of the world that have yet to make their commitments public. Only a few major developing countries, such as Mexico, have submitted pledges besides China. Notably, Brazil and India have yet to announce their INDCs, although Brazil’s leaders announced last week in an agreement with the U.S. that they would commit to generating 20 percent of the country’s electricity from non-hydroelectric renewables and restore 12 million hectares of forest by 2030. With only a few months left before the Paris climate negotiations, China’s INDC can serve as a critical model for what others can aspire to deliver.

Angel Hsu, PhD, is an assistant professor at Yale-NUS College and the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Yuqian Peng and Kaiyang Xu are masters of environmental management candidates at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.