By Kevin Mo

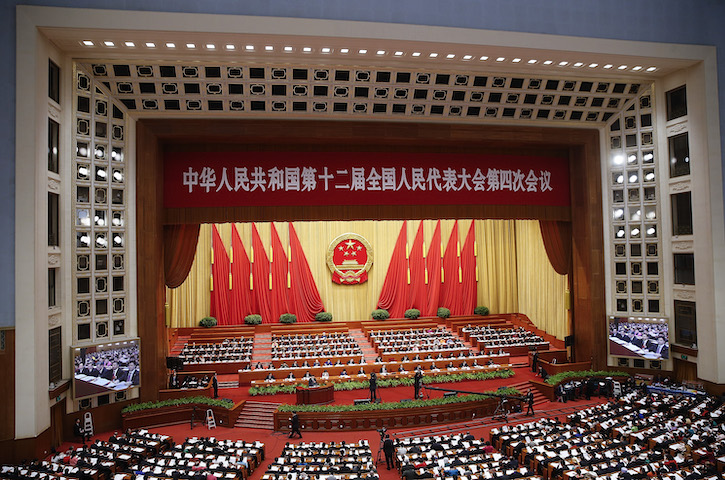

On Friday, Beijing issued a yellow alert for severe air pollution; definitely bad weather conditions to kick off China’s important annual political events: the 4th Session of the 12th National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC)—the so-called “lianghui” (meaning the two conferences).

Every year at this time, the nation’s attention is focused on the lianghui, where a series of critical issues will be debated and policies released, including details on the 13th Five-Year Plan. But this year is probably the most critical moment for China ever since it started the “reform and opening up” policy 30 years ago. Since that time, China has maintained an average of double-digit GDP growth rate, which was unprecedented and probably unrepeatable. In addition, China has avoided the 1997 and the 2008 global economic collapse, appearing invincible to any economic and financial crisis.

Not so any more. China has accepted a concept of “new normal,” admitting that lower GDP growth will be a reality for years to come. The economic growth rate was 6.9% last year, the lowest since 1990, and it is anticipated to be even lower for 2016. The stock market has dropped 50 percent from its last year’s peak, the currency has entered a cycle of depreciation, and last week Moody’s downgraded its outlook on China’s sovereign rating to ‘negative’ from ‘stable.’

This is no moment to delay reforms. This is a pivotal moment for China to take advantage of the economic slowdown to accelerate its sustainable economic transition by restructuring its heavy industry sector and expanding less carbon-intensive parts of the economy as new drivers of growth.

Facing so many economic uncertainties, will China come out of the lianghui with a continued commitment to climate issues and sustainable economic transition? On the one hand, many Chinese economists have warned that if China doesn’t continue its economic transition and deepen its reforms, the country may fall into the same ‘middle class trap’ as many other countries have before. And without significant reforms, a continued reliance on inefficient state-owned enterprises could prevent China from reaching its ambitious carbon emissions goals. On the other hand, real reforms could help China make the transition to a more services-driven economy, also improving industrial efficiencies and cutting emissions. But will the government have the courage to move toward a new economic model, which would in part entail letting inefficient and polluting industries fail?

What China does in the next 3 to 5 years may determine which direction China goes in the long term. This is no moment to delay reforms. This is a pivotal moment for China to take advantage of the economic slowdown to accelerate its sustainable economic transition by restructuring its heavy industry sector and expanding less carbon-intensive parts of the economy as new drivers of growth.

There will be about 210 representatives from the energy sector attending lianghui this year. They surely realize what challenges the energy sector will face in 2016. Take the coal industry, for example. Two days ago, Mr. Wu Yin, a retired deputy director general (vice-minister level) of the National Energy Agency said that China’s demand for coal might have already peaked. He asked the coal industry to “face the reality”—meaning that a decline is inevitable. The main coal-consuming industries are power, iron and steel, cement, and building materials, and all saw a peak in 2013. By 2030, according to government plans, coal consumption will drop to 3.6 billion tons, accounting for less than half of total energy consumption. That’s great news for the environment and China’s drive to reduce emissions. But overcapacity is a serious political problem: China has closed 7,250 coal mines during the period of 12th Five Year Plan and plans to cut 500 million tons of coal mining capacity in the next three to five years. Coming at a time of economic slowdown, the question is how to transition all of those jobs?

Overcapacity is not just limited to the coal industry. The iron and steel industry feels the same pain. In the next three years, China plans to cut 100 million to 150 million tons of production capacity. Job loss, decrease of local tax revenue, and potential social instability are concerns to be addressed before closing an iron and steel plant. Last week, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security announced that 1.8 million workers will be laid off in the coal mining, steel, and iron sectors and laid out a plan to allocate 100 billion yuan to support them – about $8,300 for each worker. This is just the first step in trying to resolve the overcapacity problem prevalent in almost all heavy-industry sectors. We can probably expect to see more plans related to this issue coming out of the lianghui.

As we follow these important meetings over the next two weeks, we hope to see signs of more policies that restore market confidence by demonstrating China’s resolution to continue its sustainable economic transition, take on challenges such as overcapacity, and to seize this moment for energy transformation.

Dr. Kevin Mo is the Managing Director of the Paulson Institute Representative Office in Beijing, in charge of climate and sustainable urbanization.